Socrates is one of history’s greatest philosophers, influencing countless generations that came after him. Many scholars and academics have analysed his life, unearthing new dimensions of the man and Dr Armand D’Angour has provided one of the most vivid depictions of Socrates in recent memory.

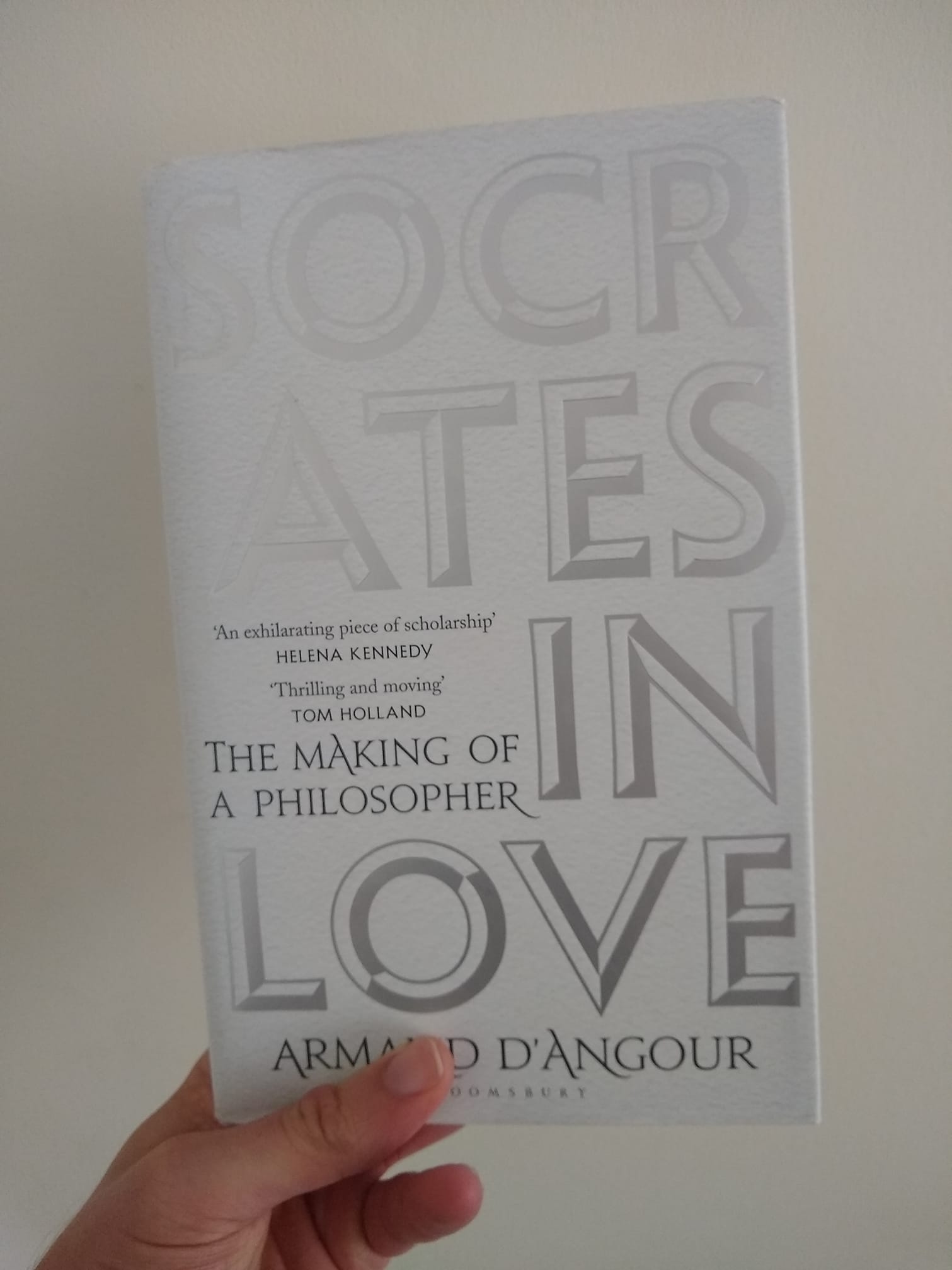

The author of Socrates In Love: The Making Of A Philosopher, D’Angour shares his thoughts on a young Socrates, how he brings philosophy into his role as a Professor of Classics and more in this wonderful interview with Stoic Athenaeum.

I appreciate you taking the time to chat Armand. Before we get dive deeper into your work, it’d be great to hear how you got your start with philosophy and if there were any particular moments in your life that drew you to studying it.

I remember being taken by philosophy from a young age. I found a multicoloured book called Philosophy Made Simple and read it with a sense of thrill and wonder. Later at school I read Plato and Presocratic philosophy in Greek and got into Popper and Wittgenstein.

I chose to do a special project on Parmenides and asked my Greek teacher for an extension to finish it because there was “so much to read”. I never finished it or handed it in…and when I met him 30 years later he raised an eyebrow and said “Where’s my Parmenides essay?”

It was a joy to discover your work through Socrates In Love: The Making Of A Philosopher and I found my own views on what I’d heard about Socrates being challenged. What inspired you to write the book?

Two things. I had been teaching Plato’s Symposium and Aristophanes’ Clouds for many years at Oxford and realised that Socrates’ early life must have been more dramatic than his later life.

Then I actually tried to dramatise (in a screenplay) what we knew from those texts and others, and realised I had to delve yet deeper into the history to understand where he had derived his philosophical ideas – especially the doctrine of love which he says is the one thing he actually knows.

Plato and Xenophon are where much of our knowledge can be derived about Socrates. What biases do you think both writers brought to their interpretations of the man?

Both were born only when Socrates was in his forties, so knew him as an older man in his 50s and 60s. So they only tell us en passant about his early life. It is clear that the main impetus for both in writing about him was to defend him against the charges for which he was executed, unfairly in their view, at the age of 70.

Both therefore present him positively overall, as a thinker and questioner, but Plato saw in him a searching philosophical mind in his own mould, while Xenophon saw him as more as a gentlemanly conversationalist such as he was. I think there are elements of truth in both – and there are other sources that add to the portrayal.

With the ideas you present of Socrates as a warrior and lover in the book, how would you like modern philosophers and academics to think about Socrates’ life as a younger man in the future?

There is more work to be done to unravel the implications of how Socrates the man might have influenced Socrates the philosopher. I hope modern academics recognise that Socrates was a man of action and passion as well as a thinker, and that the former aspects of his life are likely (and may be shown) to have had an impact on his thinking.

That means accepting, for instance, that Plato distorts Socrates’ thinking by making him more cerebral than he was; though there is in fact ample evidence in Plato for Socrates as a down-to-earth, militarily active, combative, and not unworldly individual (Plato depicts him fancying and chatting up young men, for instance, as well as indicating his relationship late in life with Xanthippe).

Your analysis of the relationship between Socrates and Aspasia is one of my favourite parts of the book. How big of a role do you think she played in the life of a young Socrates and do you think there are other examples of great philosophers being influenced by ideas posed by women?

The discovery that there was unexplored evidence for identifying Diotima as a figure Plato intended to evoke Aspasia was a eureka moment I had when writing the book. The way Diotima is introduced and effectively dated in Symposium, the meaning of her name and its connection to Pericles, and the relation of Aspasia’s reported activities to the doctrine of love Diotima was said to have once imparted to the younger Socrates, are all exciting and important new discoveries.

Aspasia may have played as big a role in Socrates’ early life and thought as she is known to have played in her husband’s, Pericles’, ideas and conduct.

If Socrates were alive today, what do you think he would make of the modern world?

I think he would be horrified and saddened by the gross materialism, irrational thinking and behaviour, and unserious politics and entertainment with which we are surrounded. He would surely choose to head to a simple retreat where he might be able think and talk with like-minded people about the meaning of life and our purpose in living.

Outside of writing, you have a history of performing as a cellist. What connections do you feel are strongest between music and philosophy?

I think of music as allowing for deeply emotional and aesthetic experiences, whereas philosophy is of a more cerebral and analytic nature. I would say they complement each other as pursuits conducive to the “good life”, rather than there being strong connections between them. The philosophy of music, ancient or modern, certainly doesn’t have any relation to my thinking when I’m performing.

In your profession as a Professor of Classics at Jesus College Oxford, what are the most important lessons that you try to instil within your students?

I think education must afford pleasure, and the truest pleasures are not superficial. Classics is a very challenging and broad subject, and requires a lot of hard learning and thinking, but if one does the work it is tremendously rewarding. I believe that study is just one component in the good life, so I would always encourage extracurricular pursuits such as music and sports, because people do well when they are motivated to do something they are good at.

If you could go back in time and have a conversation with any philosopher, who would it be and why?

Aristotle. As well as learning more about his magnificently wide-ranging ideas and his experiences as Alexander the Great’s teacher, I would ask him about both Socrates and Plato. He tells us much about the former that shows he knew that the latter had not portrayed him correctly in many ways.

Your recent project, How To Innovate: An Ancient Guide to Creative Thinking is out. What themes do you explore in the book?

The book tells some stories about how the ancient Greeks created some of their well-known cultural and technical innovations and distils from those stories (such as Archimede’s Eureka moment) some of the key principles and mechanisms that led and still lead to innovation.

These include the principle that innovation is fostered by a social and individual culture of innovation, and mechanisms such the adaptation of existing ideas, the synthesis of disparate elements into a new combination, and the disruption and critique of existing phenomena. All innovation can be shown to arise from those mechanisms and their endless permutations.

If you enjoyed this interview, check out this insightful interview with head mistress Helen Jeys on Aristotelian thinking and education.