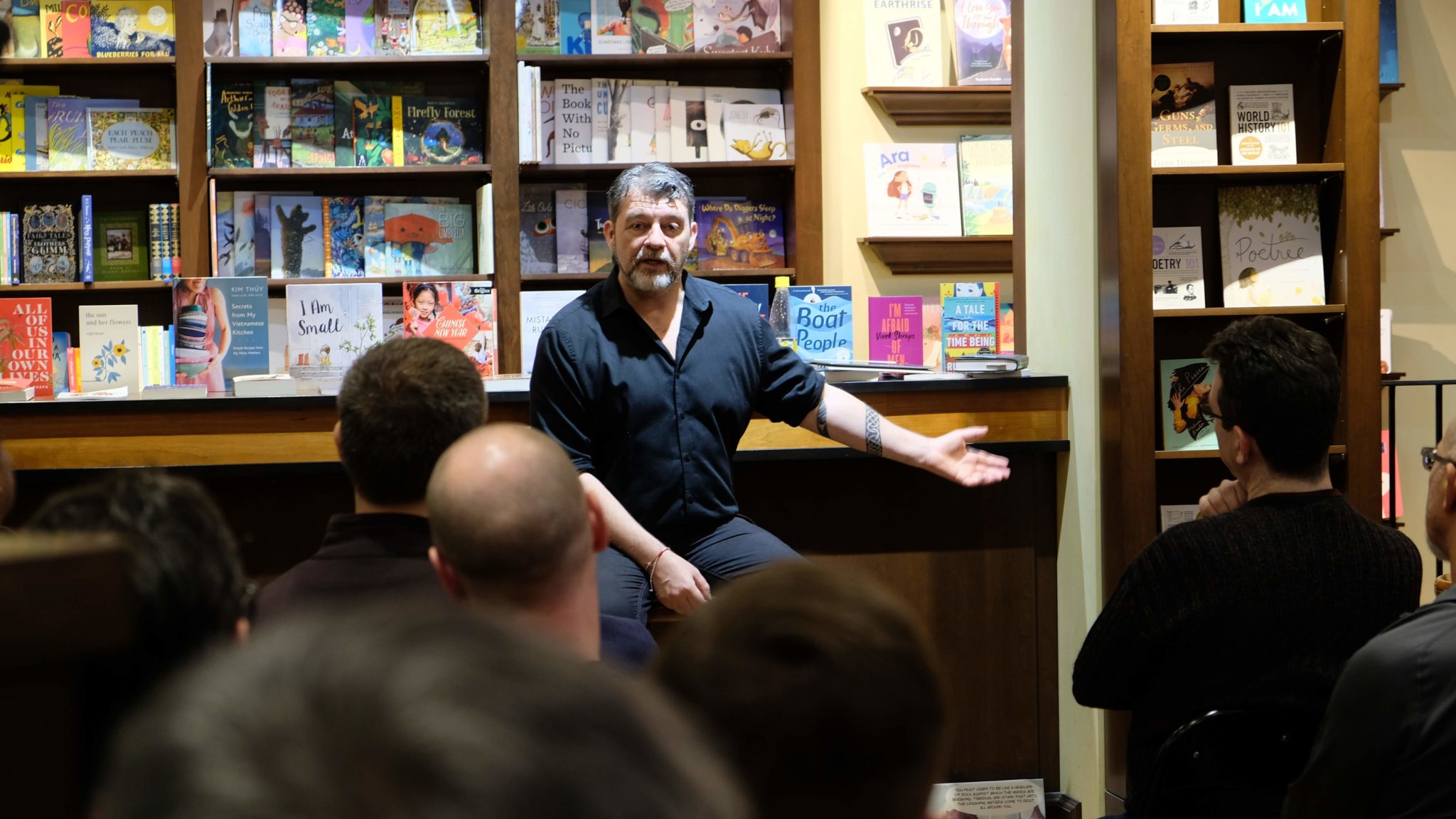

The philosophy of Stoicism has inspired the works of countless people and continues to be a driving force for many business leaders and authors today. The same can be said for psychotherapist Donald Robertson, who’s made a career out of applying the principles of Stoicism to everyday life through publications such as How To Think Like A Roman Emperor.

Robertson’s latest project is a graphic novel focused on the life of Marcus Aurelius and Stoic Athenaeum caught up with him on the process behind writing the comic. In this interview, we explore the challenges of writing a graphic novel steeped in ancient history, capturing the voice of Marcus Aurelius and how Stoicism can be interpreted through the lens of comics.

Thanks for taking the time to talk about your latest project Verissimus: The Stoic Philosophy of Marcus Aurelius. Before we get into that it’d be good to cover a bit of your background and learn more about your research and other publications that are connected to Stoicism.

I’m a cognitive-behavioural psychotherapist, although my first degree was in philosophy. So my specialism for about 25 years now has been combining ancient philosophy with modern psychology, particularly Stoicism and cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT).

I’ve written six books on philosophy and psychotherapy, and I’m working on another two at the moment: a biography of Marcus Aurelius, for Yale University Press, and the graphic novel for St Martin’s. My first book on Stoicism was called The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (Routledge) and provides an overview of the relationship between Stoicism and CBT. I also wrote a self-help book for Hodder’s Teach Yourself series called Stoicism and the Art of Happiness. I’m one of the founding members of Modern Stoicism, a nonprofit organisation founded in 2012, and run by a multidisciplinary team of volunteers, including philosophers, classicists, and psychologists.

The article you wrote about the process behind the comic is fascinating and provides a lot of great insight.

A point that stood out to me was that you mentioned you didn’t have much knowledge of comics before starting the project and that you used Scott McCloud’s Making Comics as a reference. What other types of comics and stories helped you craft your graphic novel specifically?

It was partly by chance that I was invited to write a graphic novel. I’d been working with my illustrator, Ze Nuno Fraga, on some short webcomics, and a senior editor for a major publisher saw Giclée prints that I created of the panels. I ended up getting a book deal but it was a long time since I’d really read comics or graphic novels. So I realized I needed to educate myself.

Luckily I had been a fairly voracious reader of comics as a child, and in my teens I really loved the British sci-fi comic 2000 AD, which I read every week for years. I’ve read Making Comics several times – it’s the best resource – but also his Understanding Comics, Stan Lee’s How to Write Comics, Dennis O’Neill’s The DC Comics Guide to Writing Comics, and some other books about creating comics.

I watched a few documentaries and YouTube channels about comics such as ComicTropes. I started checking out local comic shops in Toronto and chatting with friends who knew more about the comic-book medium than me.

However, to be honest, I also learned a lot by studying movies and tv shows. I watched a lot of sword and sandals movies, looking for shots that we could use in our graphic novel. I think maybe there’s a slightly epic and cinematic feel to it, for that reason. I told our editor from the outset that I wanted to avoid having pages and pages of “guys in togas and sandals talking”. So there’s a lot of action, as well as variations in scenery and in the visual appearance of different characters.

Our secret weapon, though, is Kasey Pierce of Red Pen Media and Source Point Press, who joined our team as a freelance editor. She’s an unstoppable force of nature and she’s helped to keep us on track. Kasey’s the author of the Norah comic series. I brought her onboard because I realised that, in places, Verissimus actually resembled a horror story, and Kasey knows the horror genre. However, she’s become more like a project manager, and she’s been working with us very closely to turn Verissimusinto something special.

Another point I found interesting in the article was how you focused on the concept of anger in the story to convey the visual aspects of Rome and Marcus’ life. What is your understanding of how Marcus viewed anger through the lens of Stoicism?

We know that Marcus struggled to control his own anger because he says so in the first book of his personal notes, The Meditations. He also opens the book by mentioning in the first sentence that he admired his grandfather’s freedom from anger. It’s one of the major themes that runs through The Meditations.

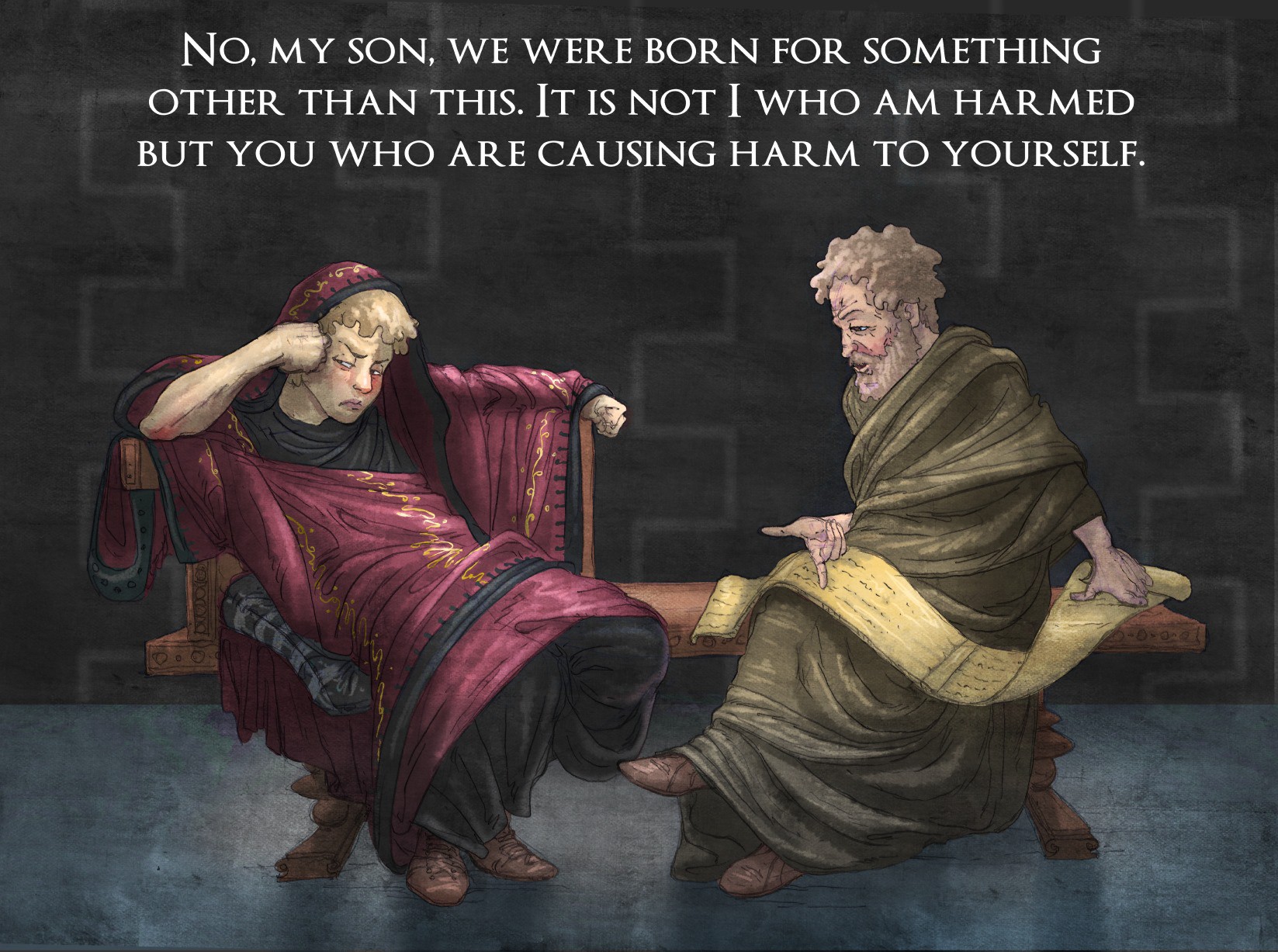

Marcus, in my view, is a pretty orthodox Stoic. He viewed anger just like other Stoics did, as a form of temporary madness, based on faulty value judgments. The Stoics, though, were more careful than we are today to distinguish between the voluntary and involuntary aspects of emotion. The first rush of anger, they thought, is like a reflex, which we share with many animals. The Stoics think that’s natural and inevitable, and neither good nor bad. The real problem is what we do next, which is voluntary.

If we go along with our initial feeling, uncritically, and add to it by making angry judgments, then we’re responsible for indulging in what the Stoics call an unhealthy (pathological) “passion”. We would do better to accept the initial feeling, with studied indifference, and wait for it to abate naturally.

The Stoics believed that pathological anger is actually a desire – the desire for revenge, i.e., the desire to harm someone we believe has acted unjustly. They think that’s crazy because it places more value upon external events, and other people, which are not up to us, than upon our own attitudes and thinking, which are up to us. The Stoics don’t want us to suppress our anger, in other words, but to see through it, and question the faulty thinking on which it’s based.

While writing the story, you spent time at Carnuntum in Austria where Marcus wrote his Meditations. Did you find it helped with putting yourself into his mindset during this research stage?

Yes. It helped to understand the scenery! Ze initially drew the terrain as mountainous but it’s actually flat there. There are also beautiful reconstructed Roman buildings, particularly a large villa, from the period we’re illustrating. There are several museums full of useful archeological finds. I was lucky to be able to interview Markus Wachter, the CEO of the archeological park, and Eduard Pollhammer, the scientific director and head of research there.

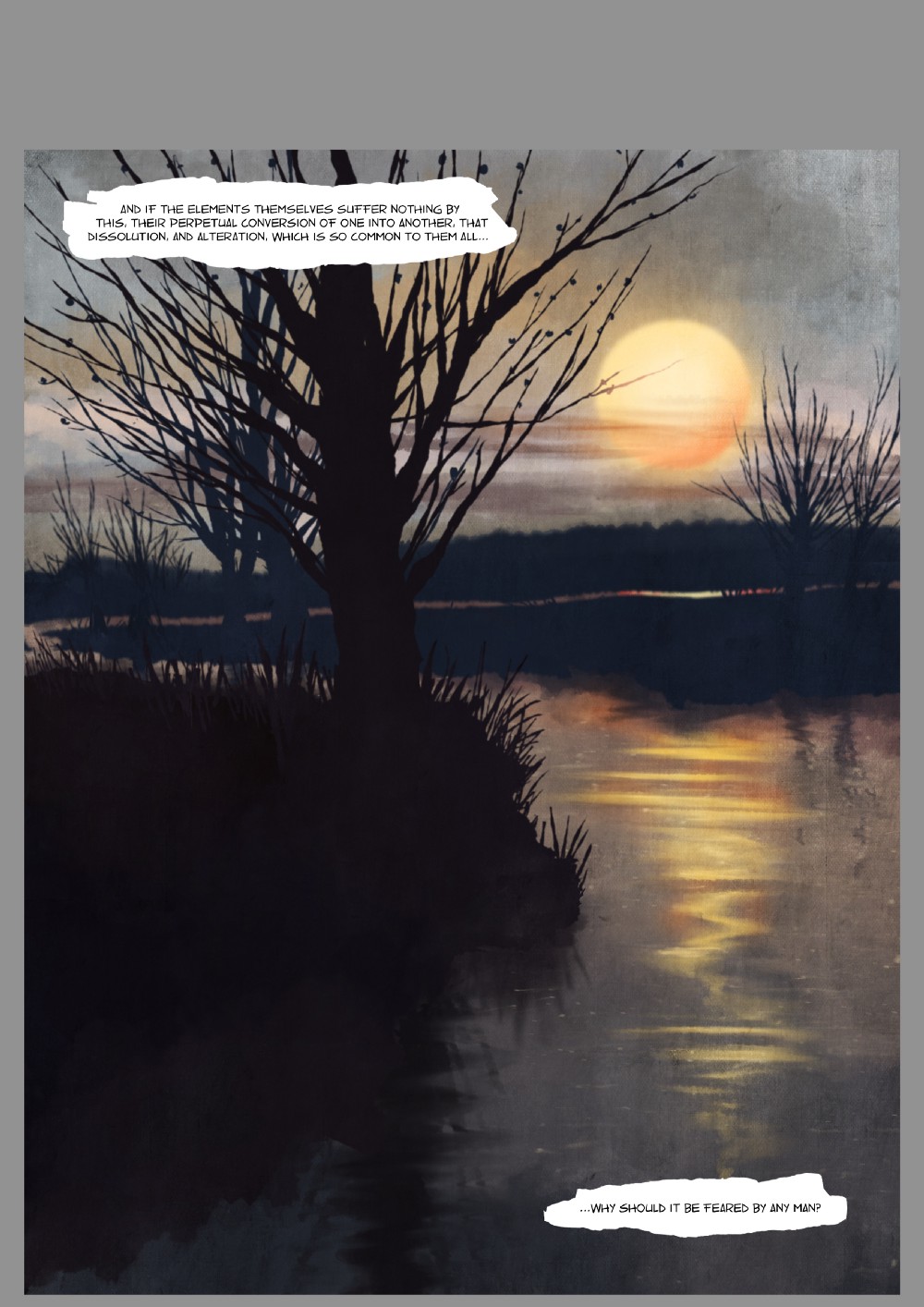

The Meditations is artfully vague. There are very few references to specific historical events in its pages, although it was written at Marcus’ HQ on the front line of the First Marcomannic War. However, we can see Marcus trying to use everyday events by turning them into metaphors for his philosophy. I try to understand how these references might have related to his actual surroundings and events in his life, for the sake of the graphic novel.

For instance, Marcus says that becoming overly-attached to any external thing would be like falling in love with one of the little birds that nests by the river – before you know it, they’ve gone, flown away and lost from sight. Well, there are many little birds in the bushes beside Fortress Carnuntum, on the banks of the Danube, and Marcus must have listened to them chirping every day, as he wrote his notes.

In another passage, he says that becoming frustrated with vicious people who do bad things would be like getting annoyed with horses for neighing – it’s just their nature. Well, there would have been thousands of horses stabled near the legionary fortress at Carnuntum so, again, that must have been a familiar experience for him.

On a darker note, he casually observes that someone who allows anger to alienate him from other people seems as unnatural to him as a head lying yards away from its own body, on the battlefield – something he mentions casually in passing, as though he’s witnessed this himself.

What advantages and challenges do you feel that comics bring to storytelling over other mediums such as book writing?

The sequential art of comic books does have many advantages over prose. Facial expressions more easily convey the significance of words, or even silent reactions to what’s being spoken. Changes in the environment can be continuous in a way that would be difficult to keep bringing up in prose.

For example, everyone who reads about Marcus Aurelius knows that a pandemic, the Antonine Plague, tore through the empire around 166 AD, and we can describe that in detail in a prose book. However, it would be tedious to keep reminding the reader about it while we go on to describe the remaining fourteen years of his reign, although the plague continued.

In a graphic novel, for instance, the plague and its consequences continue to be visible throughout subsequent chapters. Things like that are easy to show in sequential art but difficult to put into prose. It’s also easier to hint at things, perhaps, such as showing a distant figure in the background, or an object on a table, which will be used in a later panel. Light and colour, as well as shifts in perspective, can be used to transform the mood of a scene.

What kind of strengths has artist Ze Nuno Fraga brought to the project?

Ze approached me to show me his own graphic novel, originally, which was a Portuguese version of Aristophanes’ The Assemblywomen. We started working on some webcomics about Marcus Aurelius, based around Aesop’s Fables. Ze already had a knack for turning classical Greek literature into sequential art so it was a small step to take on the world of a Roman, Marcus Aurelius, who was obsessed with Greek philosophy.

Ze really brought out the personality of some of the characters and his use of colour throughout, I think, really helps to convey the mood of the scene. He recently won a national award in Portugal for best newcomer, incidentally, in comics. We’re lucky to have found him.

Throughout your extensive research of Stoicism, has your understanding of the philosophy changed overtime?

I think so, although perhaps not as much as you might expect. The core principles of Stoicism are pretty clear. (That said, people do write a lot of articles online that are very confused about them!) Studying the implications of those principles and their application to daily life, is a lifelong endeavour. I think now I have a deeper understanding of the ways in which Stoicism is indebted to earlier philosophers, such as Socrates. I don’t see it so much as standing alone in the history of Greek philosophy, but as part of a broader tradition, including Socrates, Heraclitus, Pythagoras, and the Cynics, in particular.

The main thing I’ve learned, actually, is that my initial interest in the psychological therapeutics of Stoicism was definitely justified. The Stoics made more extensive use of therapeutic concepts and techniques than any other school of ancient philosophy, and they were about two thousand years ahead of their time in that regard.

If any of the original Stoics like Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus were alive today, what kind of things would you ask them?

I’ve written three books about Marcus Aurelius now, so to be honest, I’d have a bunch of questions for him! I’d want to know a lot more about what books on philosophy he’d read, and the concepts and arguments he’d studied, and from which teachers, etc.

I’d want to know how Emperor Hadrian influenced him, as he went pretty off the rails in his latter years, and also about Marcus’ relationship with his mother, one of the most educated women in Rome at the time. Of course, as a therapist, I’d want a lot more information about Stoic therapeia, or psychotherapy: how the process worked in practice, the role of tutors in this, what contemplative practices were used, how, and when, etc.

If you could write a graphic novel about another of the ancient Stoics, who would it be and why?

I’m actually hoping the next one will be about Socrates, who was a kind of godfather to Stoicism, and my version of his life would be a bit more through a Stoic rather than the usual Platonic lens. If I had to pick an actual Stoic, the choices are limited because we don’t know anywhere near as much about most of them as we do about Marcus Aurelius – he was, as I like to put it, “a big deal back in the day”, so we have several histories of his reign and other evidence to go on.

Seneca, is the Stoic writer from whom the largest volume of texts survive, but as most scholars note, his real life was far from exemplary when it comes to Stoic values. (John Malkovich is playing Seneca, incidentally, in a forthcoming movie titled On the Creation of Earthquakes.) Epictetus is the other famous Stoic whose teachings survive today. We know very little about his life, even his name just means “acquired” because he was enslaved.

However, we do know quite a bit about Cato the Younger, aka Cato of Utica, the great Stoic hero of the Roman Republic. We have a biography of him from Plutarch that could be used but another option would be to base a graphic novel upon the famous Latin epic poem by Lucan, Seneca’s nephew, called Pharsalia, which is about the Civil War of Julius Caesar.

Cato defied Caesar and gave his life opposing Caesar’s attempt to overthrow the republic and replace it with his own dictatorship. Lucan’s poem is rather dramatic and fictionalises events but if we accept that as part of the epic genre then we’re good to go with an amazing story about war and Stoicism. I also think there’s scope for some great graphic novels that incorporate Stoicism in relation to modern life – I can think of a very obvious one but I better keep that to myself for now because I’m hoping one of my friends might turn it into a book.

What would your best advice be for anyone who’d like to create their own graphic novel based on ancient history?

Immerse yourself. Travel to the locations, if possible. Watch movies, and observe the way shots are framed and scenes constructed. Try to avoid too much dialogue by showing rather than telling, and using action where possible to complement the text. Try to vary locations where possible, and have a variety of interesting characters.

Study examples of ancient literature to find authentic phrases for the dialogue. I compiled notes – by Hercules! – on typical Roman oaths and greetings. Poetry and private letters are a great place to find examples of phrases suitable for dialogue. Don’t be afraid to construct epic scenes – we have plenty of extreme long shots of Roman sieges and marching legions. As men dominate many accounts of the ancient world, it’s useful to find creative ways to make women more prominent.

Pay attention to detail. Get advice on historical authenticity. We have an advisor who’s an expert on Roman legionary reenactments and checks our armour and weapons, and the formation of our troops, etc., for accuracy.

We made creative use of gossip and dreams, which are often reported by ancient authors but sidelines by historians. However, for instance, the gossip mentioned about Marcus Aurelius in ancient sources, is put into the mouths of patrons drinking in a Roman tavern, in Verissimus, so the reader knows that it’s of somewhat questionable veracity but nevertheless may reveal popular attitudes in an interesting way.

Lastly, if possible, for a major project like this, I think it’s a huge asset to have an editor with experience of the comic-book medium working closely with the writer and illustrator, which is how Kasey came to join us. There’s a lot of information to organise if you really want to go deep into the subject so you need to be able to work effectively as a team.